The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the greatest explosion of science fiction since the 1940s, when the genre had found its first audience here in America. In 1977, Starlog magazine published a preview of an upcoming new space-opera that was causing a buzz, a little thing called Star Wars. It was followed by the first Superman movie and the first Star Trek motion picture, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Ridley Scott brought us Alien in 1979 and Blade Runner in 1982. This last one was adapted from a Philip K. Dick story. Science-fiction film had come of age.

And Starlog magazine grew with the field. It went from a one-shot special to a quarterly frequency, to six times a year, to a monthly, in very short order. The mag’s circulation was going through the roof. We routinely sold 150,000 to 200,000 copies an issue, with special issues doing twice that amount.

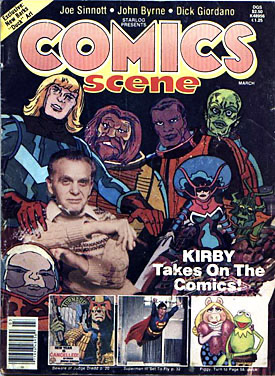

My publishers knew what this meant: it was time to take some of that money and invest it in expansion. We got bigger offices. And more staff. And in 1982, we began another pop-cultural periodical, Comics Scene magazine.

As editor in chief, I was sent to do some interviews to jumpstart the publication. I went out to California and met with Burne Hogarth, Jack Katz, and Jack Kirby. Katz had what today would be called an “indie” publication. It was a sci-fi/fantasy series called The First Kingdom. Intricately layered, it laid the groundwork for many crossover series and books to come. Hogarth was already a god of American illustration. He did the hugely popular and incredibly beautiful Tarzan newspaper strip, dailies and the full-color Sunday pages. He also had helped found New York’s School of Visual Arts. He also taught illustration, and his guidebooks, such as Dynamic Light and Shadow, are still used today.

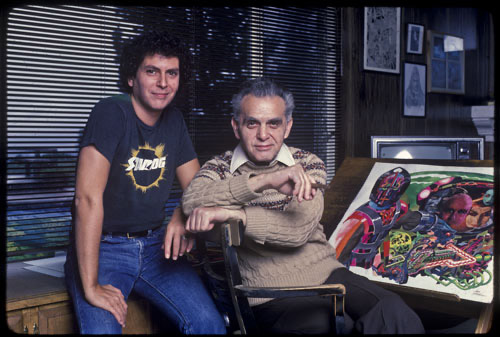

And then there was Kirby. Right behind Asimov, or perhaps side-by-side, this man was the major god in my own pantheon. And he, too, was a bona fide genius. I was fortunate enough to spend the day with him and his wife Roz, a wonderful bright, upbeat and totally dedicated partner to Jack, who she referred to as “Kirby”—although she of course knew that wasn’t his real name. A lot of young, talented Jewish kids had changed their names in the 1930s and 1940s to make them sound more American, and so Jack’s professional name was transformed from Katzenberg to Kirby.

Jack had already left Marvel by that time, and was feuding with DC as well. His “Fourth World” comics had been brilliant, but they had all ultimately been canceled by DC. Now, Jack was doing his own thing with smaller, independent houses that actually allowed creators to continue to own their titles and the rights to their work. To say that he was bitter about the way he’d been treated in the industry does not do justice to his inner rage.

But he channeled his frustrations into new energy, creating new worlds, new characters, and new comics titles.

I had a great time during that trip and came away with forever memories of meeting men whom I greatly admired. The original Comics Scene only had a two-year run, but it was great to have had the experience.